Why Investors Never Learn

“The financial memory,” argued John Kenneth Galbraith, “should be assumed to last, at a maximum, no more than 20 years.”

Just so. But why 20 years?

This is normally the time it takes for the recollection of one disaster to be erased and for some variant on previous dementia to come forward to capture the financial mind. It is also the time generally required for a new generation to enter the scene, impressed, as had been its predecessors, with its own innovative genius.

Mr. Galbraith authored these words in 1990, some 31 years ago…

Before the internet spread its net. Before asocial media. Before the Federal Reserve could clear out the memory centers… compress the attention span… and addle the judgment.

The financial memory has since shortened — from years to months.

Memories Shorten

The Great Depression etched deep, horrible grooves into investors’ memories.

Stocks only recovered their 1929 highs in 1954… 25 years later.

But following 1987’s Black Monday, the “Greenspan put” was hatched.

Thereafter the Federal Reserve was in the business of holding up the stock market — and holding down memories.

Stocks made good their 2000–01 dot-com losses in perhaps six years… and their 2008 losses in four years.

Last March, the coronavirus blew on in. Stocks endured their most vicious harpooning since 1929.

The financial press was frantic with dismal warnings of Dow 10,000 — or lower.

The pangs of painful memories began to bubble, the reverberations of financial hells past.

But Mr. Powell reached for his billy club… set to work… and bludgeoned investors into a gorgeous state of amnesia.

The harder the Federal Reserve clobbered, the more memory it knocked from skulls.

Pummeled

Trillions and trillions of dollars came battening down upon investors.

The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet has swollen from a pre-crisis $4.1 trillion to a dizzying $8.4 trillion.

The M2 money supply has expanded a furious $3 trillion within the narrow space of 18 months.

The result?

Within months of the greatest economic discombobulation since the Great Depression, the stock market recaptured all its losses.

Within a few additional months it scaled the record heights, the impossible heights — Dow 30,000 — and beyond.

Today the Dow Jones challenges 35,000.

From decades to years to months… the financial memory is thus reduced.

New Deliriums, Old Deliriums, Same Deliriums

Eighteen months after the terror, investors are trembling not from fear but from greed. Margin debt runs to record heights — nearly $850 billion (although it has declined recently).

Never before have investors borrowed so much money to purchase so many stocks. Overvalued stocks. Wildly overvalued stocks in many cases.

They have forgotten.

They have forgotten the dot-coms. They have forgotten subprime mortgages. They have forgotten — apparently — the coronavirus and its Delta variant.

A new generation of speculators has now entered the stage. As all others before it, it is taken with its own innovative genius.

This bunch speculates in Bitcoin. It joins Reddit and “short squeezes” Wall Street. It thrills to initial public offerings… and fixates upon special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs).

That is, old deliriums have given way to new deliriums.

Knocked from its wits by the Federal Reserve, this new breed’s financial memories do not extend one year.

But the generations differ only in their memory spans and their peculiar dizzyings.

The new generation is at heart the old generation. And the generation prior. And the generation prior to that.

The Good Life

Its excesses parade daily before our eyes. Columnist Kevin Williamson:

The display cases of the nation’s Rolex boutiques are stripped as bare as a San Antonio supermarket after a polar vortex. It is difficult to think of another plague that has been accompanied by quite so much high-end conspicuous consumption…

High-end Jeeps, Toyota trucks, Range Rovers, Corvettes, the Mercedes S-Class and other rolling emblems of mid-American ostentation are going as fast as they can unload them…

The wine shops are doing an astonishing trade in $750 bottles of Château Margaux, and if you want to buy a new Rolls-Royce or Lamborghini, you’ll be lucky to take delivery sometime toward the end of 2022 — and they’ll act like they’re doing you a favor.

Much of this extravagance — we remind you — transpired during the gravest economic rattle since the Great Depression.

A Form of Welfare

Yet moneyed speculators roll around in Lamborghinis. They place Rolex timepieces around their wrists. They guzzle $750 wines.

Do we begrudge the man with his Lamborghini and his Rolex timepiece and his $750 wine?

We do not. He is merely seizing the outstretched hand of Mr. Jerome Powell and his mates of the Federal Reserve.

They are slicking his palms, and he knows they are helping him along.

“You can’t fight the Fed,” he says, “so you might as well get while the getting is good.”

His judgment has proven very, very sound… to date.

Yet his grand living depends — in one sense — upon public assistance. That is, he depends upon a form of welfare.

Absent the Federal Reserve’s kindly influence, the odds are extremely low that he would be going in such style.

His luxuriance is not the product of the free market.

The trend has accelerated these past 18 months. But it stretches back decades…

Financialization of the Economy

The financial industry represented 10% of GDP in 1970. It ballooned to 20% of GDP by 2010, inflated by the helium of artificially low interest rates.

A financialized economy demands perpetually expanding credit — debt — to keep the show going.

Servicing that debt absorbs increasing amounts of society’s income. Wages wallow — and the middling classes with them. That, in turn, leaves less to save… and to invest in productive assets.

Speculation shoulders out investment.

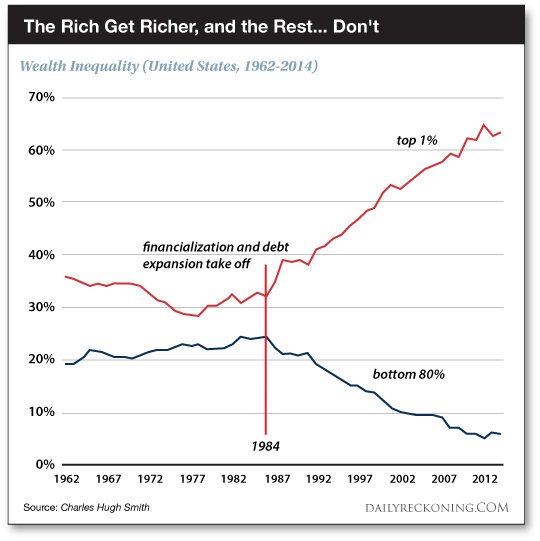

The great chasm began to open in the mid-1980s:

Does this financialization benefit the United States economy in the overall?

Economists Gerald Epstein and Juan Antonio Montecino have ransacked the numbers. These numbers reveal that financialization is, in fact, economically ruinous.

A $22.7 Trillion Drain

These gentlemen conclude the financial sector has drained trillions and trillions from the United States economy since 1990:

What has this flawed financial system cost the U.S. economy?… We estimate these costs by analyzing three components: (1) rents, or excess profits; (2) misallocation costs, or the price of diverting resources away from non-financial activities and (3) crisis costs, meaning the cost of the 2008 financial crisis. Adding these together, we estimate that the financial system will impose an excess cost of as much as $22.7 trillion between 1990 and 2023, making finance in its current form a net drag on the American economy.

Yet these gentlemen settled upon their $22.7 trillion figure before the pandemic. We are aware of no update.

But we hazard it must be an even greater enormity.

Meantime, the nation’s debt has jumped over 400% in merely 12 years. How much has national income increased over the same space? Perhaps 30%.

The economy presently requires perhaps $4.50 in debt to squeeze out $1.00 of growth.

But the Federal Reserve must keep the show running with greater debt yet — else the curtain falls and the theater goes dark.

This Time Is Different

Meantime, the financial memory shortens, Lamborghinis roll from showrooms, Rolex watches wrap around wrists, $750 wines go down gullets…

And John and Jane Doe gutter along, as they can, on what they can.

Is the business sustainable? The question is a leading question.

Today’s bubble will go alongside the South Sea Bubble… 1929… and 2000, argues legendary money man Jeremy Grantham:

The long, long bull market since 2009 has finally matured into a fully fledged epic bubble. Featuring extreme overvaluation, explosive price increases… and hysterically speculative investor behavior, I believe this event will be recorded as one of the great bubbles of financial history, right along with the South Sea Bubble, 1929 and 2000.

We hazard Mr. Grantham is correct. It is a bubble for the annals.

The latest generation of speculators has thrown aside all caution, all wariness. And they are presently enjoying a very good innings.

Yet they are likely in for a severe lesson — a lesson the wrathful gods are eager to read them.

“Experience runs a hard school,” said old Ben Franklin… “but fools will learn in no other.”

Regards,

Brian Maher

Managing Editor, The Daily Reckoning

Comments: