How This Bank Got Wiped off the Map

I was looking through my old files and remembered that I hadn’t told you this story yet.

When people ask me why I’m so against shorting options, this is what I tell them.

I’ll elaborate on what can happen — though admittedly very rarely does – when you’re short volatility and you don’t know what you’re doing.

The Rogue Trader

Nick Leeson was an ordinary boy from the ordinary London suburb of Watford. He was going to live an ordinary life until he got the opportunity to work in The City. That’s The City of London, where serious international banking gets done. It’s the British bastion of capitalism, whose profits pay for the folly of the British Welfare State.

But Nick didn’t have the right background or proper accent to succeed there. So, when he was given the opportunity to move to Singapore, he jumped at the chance.

As a side note, when mediocre bankers are sent from London to Hong Kong, they’re pejoratively called FILTH — Failed In London, Try Hong Kong. Hint, hint…

Nick got on a plane and went to Singapore, where he was simultaneously named a floor trader and Head of Settlements. In the early 90s, that nonsense could happen. Let me confirm: it means he was responsible for checking his trades. And yes, you’re right; it was a recipe for disaster.

Without overegging the pudding, let me get straight to the trades that brought down Barings Bank, HM The Queen’s Bank, in 1995.

Much of this is by memory, as my edition of Rogue Trader, Leeson’s autobiography, was lost in one of my many moves. Thus, any errors are my own.

Straddle This!

I’m going to proceed in a plain English manner, not making it too geeky or Greeky. If you’re a pro, please forgive me for the oversimplification.

First, let’s get long.

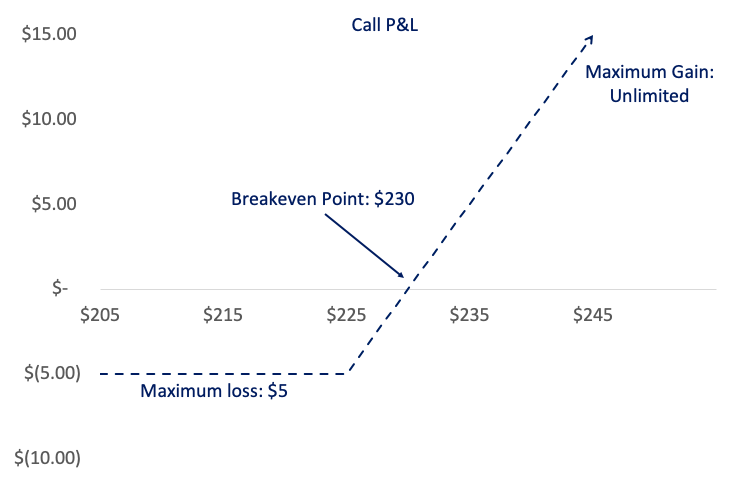

This is the payoff profile of a long call position at expiry. It’s a bullish trade. In this case, the call buyer pays $5 per share for the right to buy 100 shares later at $225. Therefore, the breakeven point is $5 + $225 = $230.

The buyer can only lose his premium, no more. That’s still 100%, to be sure, but it’s not as much as he may lose holding the shares.

The upside is unlimited. Think TSLA call buyers and how much they made in the recent past!

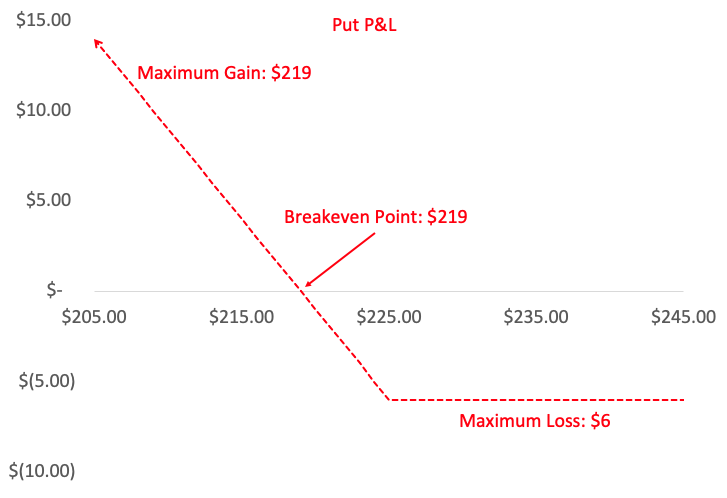

Next is a long put option.

A put option is where the buyer has the right to sell shares at a specific price in the future. In this case, the buyer paid $6 for the right to sell these shares for $225.

This is a bearish trade, as the buyer must think the price will decrease. The breakeven point is $225 – $6 = $219. That is also the maximum gain, as it’s not unlimited (though it’ll feel almost as good)!

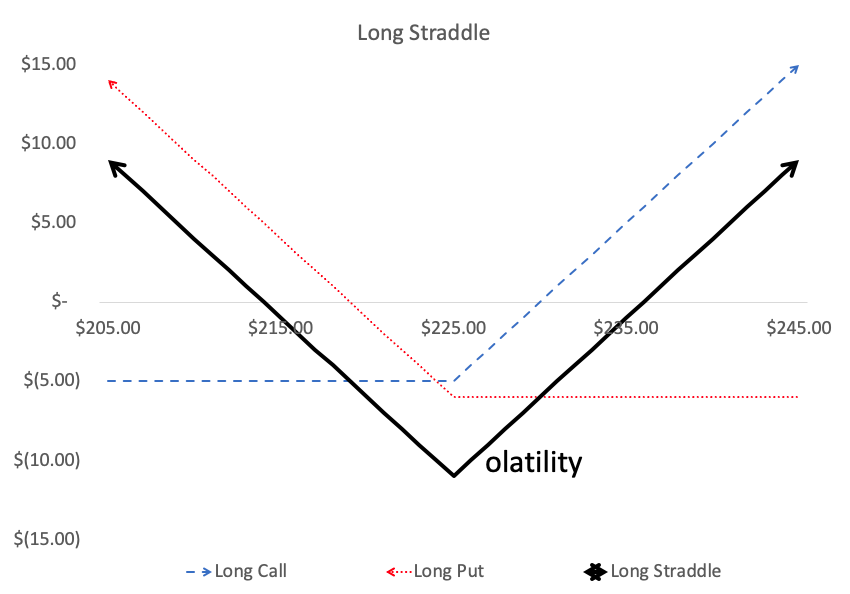

So, a long call and a long put, separately, are directional trades. But what happens when we put them together? Remember, these calls and puts will have the same underlying, strike price, and expiry.

Et voila! You’ve got a volatility trade! That is, you’re long volatility.

(I always write the “volatility” next to the payoff profile to make it easier for grads to remember.)

Looking at that payoff profile, you see something obvious: it doesn’t matter which direction the underlying goes, as long as it goes far.

So, you’ve got the unlimited gain potential from the call. And you’ve got the limited but substantial potential gain from the put. Thus, there are two breakeven points. This will be the strike price plus and minus the combined premiums.

The upside breakeven point is $225 + $11 = $236. The downside breakeven point is $225 – $11 = $214.

As long as the underlying either goes up beyond $236 or down below $214, you will make money.

Of course, the pros will manage these trades minute to minute and adjust accordingly. However, this is something retail investors, who have other jobs, will find exceedingly difficult to do.

But for now, know that a long straddle is a long volatility trade.

Derivatives Are a Zero-Sum Game

Derivatives are a zero-sum game. That means no wealth is created or destroyed by trading them. Of course, there are winners, and there are losers. It’s capitalism at its very finest. But overall, nothing is lost.

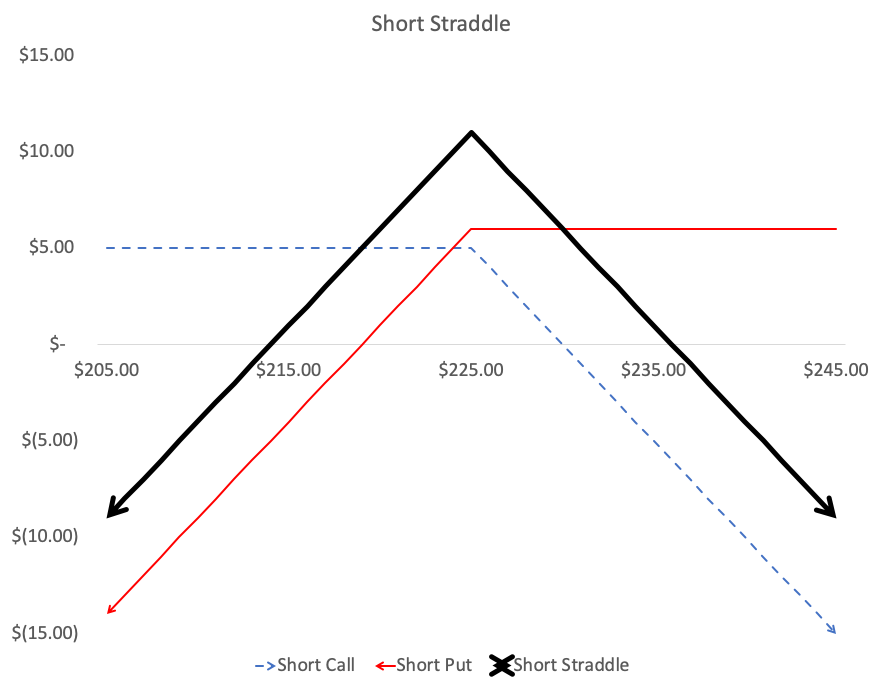

That means if you can buy a straddle, then someone must have sold it to you.

Someone like, say, Nick Leeson.

To illustrate, let’s take the long straddle we just looked at and flip it upside down.

It’s the exact same trade but from the seller’s perspective.

Let me ask you this: what’s the best thing that can happen to the seller?

Answer: nothing.

Literally.

If the straddle expires at $225, the seller will keep the $11 per share premium. Anywhere else, he doesn’t maximize his gain. Below $214 and above $236, he loses money.

Again, if a pro entered this trade, he’d keep his eye on it and manage it accordingly. He can use stop-loss orders, close out a side, or turn the straddle into an iron butterfly. Don’t worry about these things right now.

Because if your name is in God’s book on a particular day, he will get you no matter what. And that happened to Nick Leeson.

How Straddles Killed Nick Leeson and Barings Bank

Leeson was already down.

He was supposed to be running an arbitrage operation, taking no risk. But he couldn’t help himself. Leeson already racked up millions in losses. Moreover, he was losing nearly from his first day in the office in 1992.

It just turned 1995, and he was running out of options – no pun intended.

So how could he get that money back without incurring much more risk?

Boom! He could sell straddles!

That would let him take in the premium from both the calls and puts. The markets are quiet anyway, so it’s a sure thing.

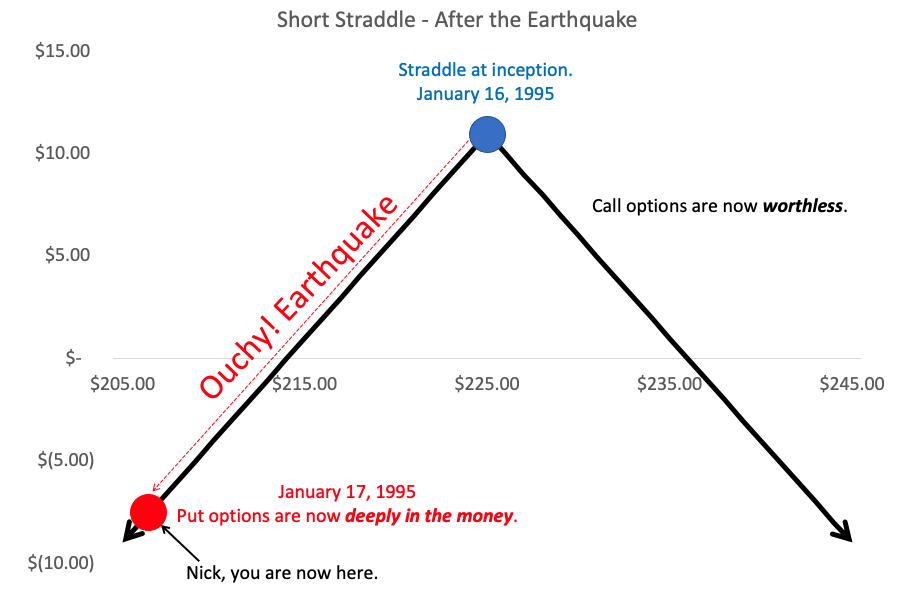

The date was January 16, 1995. Leeson sold a bunch of straddles on the Nikkei Index.

He probably went to Harry’s Bar on Boat Quay after work, thinking all was well.

Incidentally, Harry’s is next to my favorite SG watering hole, The Penny Black. Harry’s used to have a plaque on the bar that read, “Here sat Nick Leeson.” I saw it myself!

Then, in the early hours of January 17, 1995, the unthinkable happened.

The Kobe Earthquake struck.

Leeson, already down GBP 208 million, was crushed. The Nikkei gapped down on the open. Of course, the call options would expire worthless, but he was now short deeply in-the-money puts.

To counteract this, Leeson bought futures as the market “couldn’t go down anymore.” But, of course, it did — much, much more.

Nick Leeson’s losses totaled GBP 827 million, about $1.4 billion. That doesn’t sound like much now, but it was enough to wipe Barings, The Queen’s Bank, from the map.

A friend once told me of an event he held in Singapore. A member of the Royal Family was present to open the event. My friend pointed out the window onto Raffles Place and said, “That’s where Barings office used to be.” The reply was, “My family lost a lot of money that day.”

That is the story of Nick Leeson, told as plainly and as “Greeklessly” as I can.

It’s a great cautionary tale to retail options traders and professionals alike. Heck, it can be said that Leeson inadvertently wrote today’s derivatives regulatory structure.

The upshot is there are far better, less risky and less stressful ways to participate in the market than by shorting options.

Comments: